|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

|

Pioneer

Cemeteries and Their Stories, Madison County, Indiana |

|

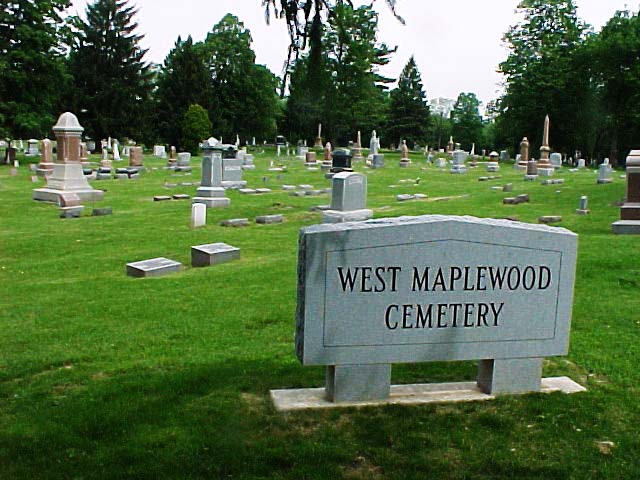

aka Anderson/City/Old Maplewood (which includes the removed Tharp and Bolivar/City cemeteries)

Location: northwest corner of Grand Avenue and Alexandria Pike in Anderson

|

West Maplewood today is a beautiful repository of loved ones and a stone library of architectural styles. From the simple rectangular slabs of the early 1800s, through the ornately decorated carvings of the Victorians, to the stone blocks of the early 20th century, West Maplewood provides a walk through the fashions and culture of the past. |

|

Overlooking the White River, the hill that is now part of West Maplewood was used for burials and the re-interment of the earlier Bolivar or City Cemetery and the Tharp Cemetery, both started in the 1830s. Many of the grave markers from these earlier burial grounds are still nicely preserved. James Tharp's stone from 1846 is an excellent example of the Federal Period's severe styling. This is a substantial tablet, almost three feet high and five inches thick, of brown granite. Granite, while hard to cut, retains the incising better than the softer white stone used from the middle of the 19th century on. Even the weeping willows and urns at the top are still beautifully visible after 160 years. |

|

|

James is next to his

parents Collins and Esther Tharp. They donated property for the first church in Andersontown, the Methodist

Episcopal Church, as well as the land for one of the city's firs |

|

|

Also from the early 19th century, Mary Stephenson Kindle's stone may be missing its top, but it has everything a genealogist could want: "Sacred to the memory of Mary, daughter of John and Mary Stephenson and wife of James A. Kindle, she was born in Warren County, Ohio, November 26, 1810, and departed this life...October 10, 1838." Often, stones from the early and middle 19th century will have additional family information. The death date of 1838 would mean that Mary was one of those initially buried in one of the earlier "city cemeteries" and later re-interred at West Maplewood after 1863. |

|

|

|

Elizabeth Pugh's stone also from 1838, on the left, and those of family members, on the right, show the beginnings of Victorian styling: the rounded tops decorated with flower motifs. Elizabeth's is a taller marker measuring around three feet high; those on the right are closer to two feet. This short, thick variety seemed to be popular in the 1840s. Evan Pugh's reads "died 1846," and Mrs. Joseph Pugh's reads "1849."

|

|

Hannah Irish Makepeace's stone is also early Victorian in style and unique among the gravestones of pioneers and settlers of Madison County. The personal information is not incised, but each character is sculpted out of the stone, giving three layers to the face. Scrolls have been added to trim the inside of the tablet's front, and the name lines repeat the top's curve. Hannah was the wife of early Anderson entrepreneur Alfred Makepeace. She died in 1858. Hannah was the daughter of Fall Creek Township pioneer James Irish and his wife Elizabeth Dibble. |

|

Descendant Tricia Matthew in Wisconsin sent Hannah Irish Makepeace's obituary from The Standard, April 23, 1858:

"Hannah Makepeace died in Anderson on the 18th, after a lingering illness, aged 48. The deceased was one of the oldest inhabitants of Anderson, having lived here since her marriage, about 30 years ago[1828]. At that time the court house square was a forest, and there were but few dwellings in the town. She, with her husband have, therefore, shared the privations, toils, and troubles incident to the settlement of a new country, and have as a reward for an industrious life accumulated much of the world's goods. She was the mother of a large family of children, to whom she had endeared herself by her many amiable qualities, who have now to mourn their irreparable loss. She had gained the esteem of their neighbors as was attested by the respect shown the family on the occasion of her burial."

|

|

|

While the Federal style was

straight and severe, the Victorians of mid and late 19th century enjoyed curved

lines and an abundance of decoration. Mollie Brown's gravestone, at left,

is an excellent example of high Victorian style. Th e

outline and forms have flowing, rounded lines and include

acanthus leaves, ribbon, and rose. The rose represents victory, pride, and

triumphant love. The

stone reads, "Mollie, wife of ...Brown, died Jan. 25, 1865, aged 29Y 6M 19D."

Viola's, in the middle, has her personal data etched on a scroll topped by a

wreath of roses. The stone on the right, while difficult to read,

displays roses under the arched cornice crowned with petals. The medallion

contains the personal data framed by rope and tassels.

e

outline and forms have flowing, rounded lines and include

acanthus leaves, ribbon, and rose. The rose represents victory, pride, and

triumphant love. The

stone reads, "Mollie, wife of ...Brown, died Jan. 25, 1865, aged 29Y 6M 19D."

Viola's, in the middle, has her personal data etched on a scroll topped by a

wreath of roses. The stone on the right, while difficult to read,

displays roses under the arched cornice crowned with petals. The medallion

contains the personal data framed by rope and tassels.

|

This marker for a member of the Peter H. Lemon family is another excellent example of high Victorian style. Although easier to sculpt and cut, the white, softer marble, popular during the period, shows the destruction incurred from time and weather. The stone has broken and in places has faded and dissolved. A trial for genealogists, stones made of this material often lose the valuable family information sometimes included. Unfortunately, it looks like this stone once held an entire story. The image at the top, left, was probably an angel. |

|

|

|

|

|

The hand was a popular memorial motif for Victorians. The most common image found on 19th century gravestones is that of a hand with index finger pointing heavenward. This meant that the soul of the departed was going to heaven or that the living should be more responsible for where they would spend the afterlife. Clasped hands, far left and right, symbolized the partnership of husband and wife on earth. A palm holding a small book or message, middle left, represented religious fervor. The hand drooping down with a broken link, middle right, stood for the languishing sorrow for the family member now separated. The three links represented the trinity and faith.

|

From the same carver or company, Julia Dusang's stone, at right, and Solomon Templin's, at left, are beautifully preserved in color and crispness. Julia's shows the bible which represents her religious faith; Solomon's adds the compass and ruler which indicate that he was a Mason. |

|

To Victorians, an urn--whether two

dimensional like the ones on James Tharp's stone above or three dimensional like the one at righ

stone above or three dimensional like the one at righ t--represents the decay of

the body: mortality. The drape, often included, would symbolize mourning

for the one who has passed away. Other popular images were a winged face,

which stood for the soul in flight, a female figure (without wings), which

represented sorrow, an anchor, which indicated hope, and a sheaf of wheat,

which symbolized a fruitful life.

t--represents the decay of

the body: mortality. The drape, often included, would symbolize mourning

for the one who has passed away. Other popular images were a winged face,

which stood for the soul in flight, a female figure (without wings), which

represented sorrow, an anchor, which indicated hope, and a sheaf of wheat,

which symbolized a fruitful life.

Some Victorian stones have multiple symbols, like the one on the left: a bible and perhaps a hymnal for faith, roses for love, and a drape for mourning. This period variety, a "podium"-- which is topped with something, often draped, having flowers and many times a medallion containing the personal information-- was another popular style during the mid to late 19th century.

Religious verses were also popular additions; however, because of the soft white stone used at this time, the words are now often difficult and sometimes impossible to read.

|

|

|

|

The death toll for children and infants in the 1800s was often as high as one in three. As seen above and at left, it was customary to use a much smaller stone, often with a lamb or angel, for the graves of young ones.

|

|

The ornate stones for one year old Lillian, above, and young adult Joseph, right, are complete with stacked rocks, scrolls, and lilies. The lilies stand for purity or chastity, and this variety was used so often at funerals and on markers that it is now sometimes referred to as a "death lily." Joseph's cross represents his religious faith, of course. |

|

|

The Victorian's use of images from nature on memorial architecture--like the rocks and flowers depicted above--reached a zenith toward the end of the 19th century with this version, at left. The VanWinkle family plot marker is a "tree cut-off." The individual members' stones, front and mid-ground, are rendered as the branches from the tree. |

|

In contrast to the ornately decorated markers above are the stylistically simple pillars of Andrew, 1810-1876, and Jane, 1815-1874, Lemon. An earlier rectangular tablet from the 1850s can be seen leaning against the right marker. While of simple styling, the Victorian's fondness for symbolism is still evident. Obelisks, like these, traditionally represented rebirth and the spiritual connection between heaven and earth. Andrew and Jane were both born in Ohio and, like so many others, took advantage of the development occurring in east-central Indiana. They and their young family arrived in Madison County in the early 1840s. Along the Lindberg Road between Anderson and Chesterfield, they developed a large farm that straddled Anderson and Union townships. Because their house was located in the Anderson Township part of the property, they and their family members are listed in the census records for that township. |

|

|

By far, the most common style of grave marker used in the first two-thirds of the 19th century for the average citizen--especially for those living in less affluent, rural areas--is the small, simple tablet like the one pictured at left and below. "Mary [Gustin] wife of John Stephenson died February 27, 1851, 71 ys 8 ms 20 ds"--just the inexpensive basics. Using the birth date instead of the person's age became the norm during the Civil War. Some transitional stones actually have all three: birth date, death date, and age. |

|

|

Starting in the 1840s, a soft white marble became more popular than the granite used previously; the marble was easier to cut. Sara Kindle's tablet type marker, left, has faded so much that her data is barely legible. She died "April 4, 1845 aged 27ys 7m & 28d." |

By contrast, right, Hannah Jane's extra tall vertical is still crisply preserved, and it has additional genealogy. She was the "daughter of John and Angeline Gallemore & wife of Philip S. Hayward, was born Feb. 18, 1836 died Feb. 27, 1854 aged 18 Years & 9Ds." Genealogists could not ask for more. |

|

|

|

|

As demonstrated by the Gustin stones above, styles began changing in the late 1880s and 90s--from the ornately decorated markers with curving lines of the mid-Victorians to the Edwardians' less ornate blocks and pillars. The natural forms, such as Jonathan's oak leaves on the left, gradually gave way to more architectural features such as the pediments seen on the family plot markers below. |

|

|

Another important change occurred in the last years of the 1800s because of the preference for chunky squares and rectangles: instead of standing thin slabs upright on end as had been the custom, blocky grave markers could merely rest on top of the earth. This form of setting stones is still used today.

|

|

Gertrude Pauline and Charles Ingersoll Hilligoss both died in the 1880s. Their father Dr. Hilligoss commissioned these stone portraits that face busy Grand Avenue. The statues can easily be seen by travelers. The column Charles is leaning on symbolizes a noble life; Gertrude's book stands for the divine word. "The Children" have become something of a land mark in the north Anderson area. Their likenesses are always decorated, as seen in this photo, with the appropriate symbols and garlands for the holiday or season. One does not have to be a relative or cemetery commissioner to appreciate the people who have come before. |

|

|

|

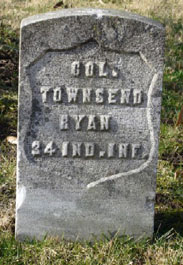

The stones above are not Federal, Victorian, or Edwardian. They are the military markers designed for veterans of the Civil War. These thick, gray to white tablets, on which a shield incases the personal data, can be seen from a distance as indicating the graves of Civil War veterans. From one family, the Ryans represent the many Madison County soldiers who helped preserve the Union.

The first public cemetery for the city of Anderson was ordered in 1832. It was situated at the end of what was called at that time Bolivar Street (now east end of 10th St., east side of Fletcher; see map on Anderson Township page) and so was referred to as the Bolivar Cemetery and later the City Cemetery. This first official graveyard for Anderson was supposedly purchased from John Berry who had initially bought the entire village from the Delaware, platted the town of Anderson, and donated city blocks for the county seat. With the construction of the Pittsburg, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad almost two decades later, the Bolivar Cemetery had to be moved. Most of the remains were re-interred in the Tharp/Thorpe Cemetery located on 11th Street and Delaware. Unfortunately, some bodies buried in the Bolivar were included in the fill dirt used for building up the railroad bed.

|

At left, the first cemetery for Anderson residents was called City or Bolivar Cemetery. It was on the west bank of White River at the end of what was once called Bolivar Street. Undergoing many changes over the decades, this location is now used for a parking lot for business offices. When mid 19th century necessity demanded, those buried at the City Cemetery were re-interred at the Tharp (see below). |

The Tharp Cemetery had been in use since 1827 when the Methodist Episcopal Church needed a cemetery for its members. Collins Tharp had laid out the cemetery's design. With the expansion of Andersontown, though, the Tharp had to give way to progress. Those buried in the Tharp were re-interred in 1863 in what was referred to as the "New City Cemetery" north of Anderson at the corner of Grand Avenue and Alexandria Pike: this was Maplewood. In 1902, to meet Anderson's still growing needs, a much larger, modern cemetery was developed to the east of the original and also named Maplewood. The new, business-like concern took over the care of old Maplewood and renamed it West Maplewood.

One of the burials

re-interred at Maplewood, the new city cemetery, was William Allen, one of the

earliest settlers to the area. William was born in Philadelphia in 1791.

He served during the War of 1812, moved afterward to Ohio in 1816, and traveled

further west to the New Purchase in 1821, settling two miles east of

Andersontown. He brought with him a wife and growing family of ten

children and entered purchase of his homestead June 19, 1823. Mr. Allen

held several important positions for the new little village of Andersontown.

He was a justice of the peace, a school teacher, a correspondent for the

War Department during the Indian Massacre,

a county

commissioner, and the first county assessor. The first election was held

at his home. William also had the distinction of owning the first whipsaw

in the county--high technology for pioneers. He sawed the lumber for the

Makepeace mill in Chesterfield, a mill being indispensable in the production of

area grains, wool, and lumber. Mr. Allen is described by historian Harden

as being tall and slim, "well informed and of good business qualifications,

which were appreciated at that early day." William died in 1829. His

son John was responsible for seeing that his father's remains were removed and

re-interred in the beauty and safety of Maplewood.

family of ten

children and entered purchase of his homestead June 19, 1823. Mr. Allen

held several important positions for the new little village of Andersontown.

He was a justice of the peace, a school teacher, a correspondent for the

War Department during the Indian Massacre,

a county

commissioner, and the first county assessor. The first election was held

at his home. William also had the distinction of owning the first whipsaw

in the county--high technology for pioneers. He sawed the lumber for the

Makepeace mill in Chesterfield, a mill being indispensable in the production of

area grains, wool, and lumber. Mr. Allen is described by historian Harden

as being tall and slim, "well informed and of good business qualifications,

which were appreciated at that early day." William died in 1829. His

son John was responsible for seeing that his father's remains were removed and

re-interred in the beauty and safety of Maplewood.

|

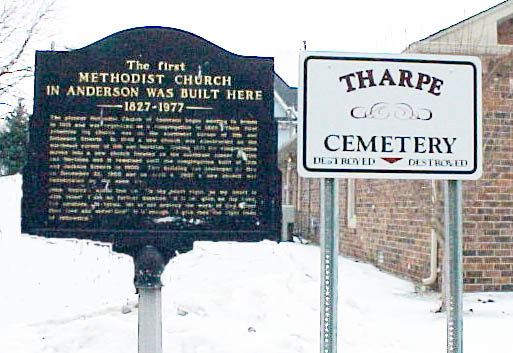

Removed in 1863 to give way for Anderson's development, the Tharp/Thorpe/Tharpe Cemetery was located at Delaware and 11th streets. It was the burial ground for members of the first organized church in Anderson, the Methodist Episcopal. The land for both the church and its adjoining cemetery was donated by Collins Tharp. The MCCC sign and the Indiana Historic Marker, pictured right, are on the east side of the brick building housing the Chamber of Commerce, seen here in the background. The signs can be glimpsed while traveling south on what is now Brown-Delaware. The removed graves and their markers can be seen in the old section of West Maplewood. |

|

One of Anderson's first prominent citizens was Nineveh Berry, a veteran of both the Mexican-American and Civil wars. Nineveh Berry was the son of city founder John Berry. Nineveh was born in 1804 when the Berry family was living in Ohio. He was eighteen or nineteen when his father laid out the plat for Andersontown. Nineveh was the city's first postmaster. Mr. N. Berry operated the post office out of his father's house. The mail arrived on horseback and came just once a week. Nineveh was considered a "walking post office" because he carried the mail to his customers in his hat. Therefore, Andersontown had one of the first free mail delivery systems in Indiana. Nineveh also served the Madison County community as county recorder for seven years, county treasurer for two years, deputy sheriff, and county surveyor. As surveyor, Mr. Berry laid out the plat for Alexandria in Monroe Township.

Additionally, Nineveh Berry was a military man. He served in Indiana's armed forces, attained the rank of colonel, and was always referred to by that title. He was appointed September 8, 1847, for duty in the Mexican-American War and saw action in several battles. Later for the Civil War, Nineveh Berry enlisted, in spite of his age, and served until his health was compromised.

Nineveh was over six feet tall, weighed over 200 pounds, and had a commanding appearance. Something of a county historian, himself, Nineveh is given credit by author Samuel Harden for passing on many recollections of Anderson's past. As Harden summarizes, "Throughout all his associations, both public and private, he [Berry] has maintained the honor and respectability to all his fellow citizens..." Col. Nineveh Berry--early settler, community leader, soldier, Hoosier character--died in 1883. He is pictured in the 1880 History of Madison County, Indiana on page 87.

|

The Berry family has three stones in West Maplewood. The one for Nineveh and his wife Hannah has the round column--representing noble lives--leaning next to the base, ready for replacement. The stone to the right is the government issue marker signifying Nineveh Berry's service in the Civil War. The pillar to the left is for Nineveh and Hannah's son James died in the Civil War in 1862. There are inscriptions and information on both of the taller stones, but the words, alas, are very faded. |

The present answers the past. In 1974, the MCHS's Cemetery Conditions Committee was making transcriptions of grave markers. Volunteer Robert Hensley was working on the oldest section of West Maplewood, that which includes the graves removed from Anderson's previous places of burial. At the end of his typed report, Robert made special mention of two early stones:

"The markers being very old...of the type of the early 1800s have these inscriptions.

"Hannah Harpold

Wife of Daniel

Died July 18, 1852

Age 71 Yrs. 1 Mo. 25 D.

_______________________________

"In Memory of Daniel Harpold

Who was born April 12

and deceased Dec. 19, 1839

Age. 51 yrs. 11M. & 26 D.

Is there any history connected with these?"

Yes, Robert, there is some important Anderson history here. The Harpolds are listed as among the first settlers to Andersontown, and Daniel was the builder of the city's very first court house.

|

The obelisk, right, for Col. William Young and his wife Jemima is in excellent condition. William's data is on the west face; Jemima's on the south. William is listed along with Christopher and Isaac Young as a first land owner in Anderson Township, arriving in the 1820s. Historian Samuel Harden continues: "Colonel William Young, a very popular man, came to the county when a young man. He was quite well known throughout the county. He represented Madison County in the Indiana Legislature in 1846-47. He died August 20, 1863, aged sixty-six years, three months and twenty days. His wife Jemina, died November 23, 1851, aged fifty-two years, seven months and fifteen days; both buried at the Anderson cemetery [West Maplewood]." |

|

|

While most histories written during the 19th century focused on men, some women were also noted. "Susannah wife of Martin Brown" was a McAllister. She was born c. 1798 and "died Jan. 21, 1866 aged 68Y. 1M. 18D." Her families' stories are told on the McAllister and Hardy-Culp cemetery pages. |

|

It should also be noted that resting at West Maplewood are three of Madison County's historians. Edith Cascadden focused on the history of Lapel and Fishersburg. Her work is referenced on the Stony Creek Township history page. Also buried at this cemetery is John L. Forkner, businessman, banker, and mayor of Anderson for two terms in the early 1900s. Forkner was born in 1844 and died in 1926. He is the author and editor of the 1914 History of Madison County, Indiana. Samuel Harden, born in 1843, was the area's first chronicler, publishing his History of Madison County, Indiana in 1874. Harden expanded upon this work with the publication of The Pioneer in 1895 shortly before his death. A veteran of the Civil War, Harden additionally produced The Boys in Blue about the county's soldiers in that conflict. The works of both Forkner and Harden are among the literary sources used throughout this web site for the biographical and historical information.

|

|

|

West Maplewood adorns Anderson, IN, with eclectic beauty, a mixture of period memorial styles--Federal, Victorian, Edwardian, simple and lavish, symbolic and restrained, past and present. The cemetery, itself, symbolizes the area's history and preserves the final resting places of many pioneers and early settlers.

(For more information concerning 19th century gravestone styles, go to the Tomb with a View web site: <http://members.aol.com/TombView/symbol2.html>.) |

|

Click here for a list in pdf format of burials with headstones.